Regenerative Farming goals

In the winter months we get downtime to shape and frame the season ahead. One question that continues to be front of mind is: how we can leverage our actions on one small farm to reduce climate change? It’s anxiety provoking to see the world temps hit record highs year after year, to know that melting of glaciers and arctic ice sheets are impacting our oceans, to see firsthand the strange weather patterns and superstorms that come our way. So we take the opportunities wherever we can, and in the most impactful ways we can.

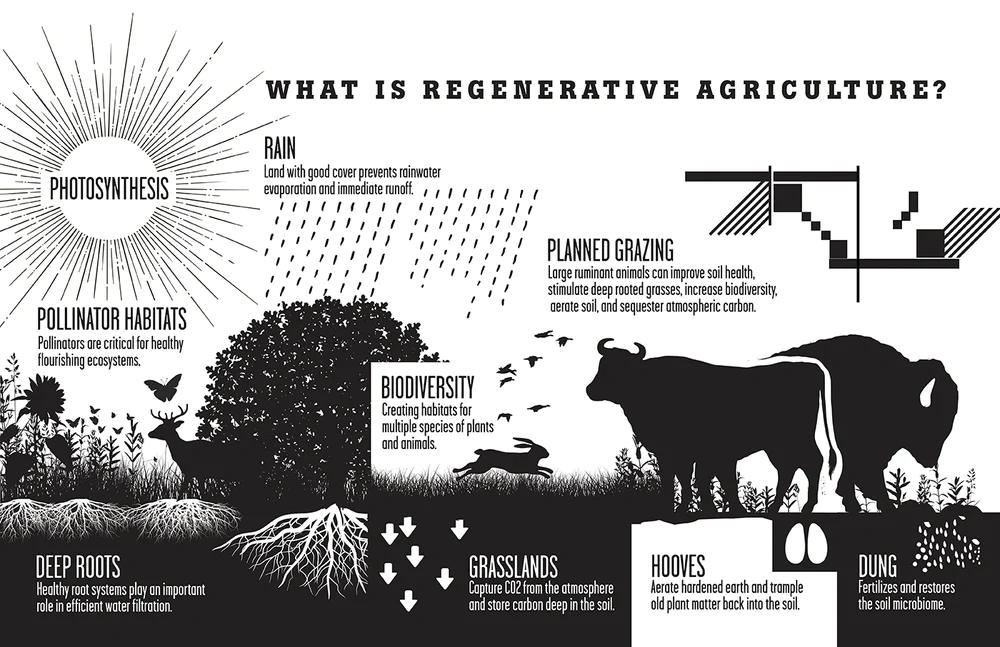

Regenerative farming practices are designed to work in harmony with nature to build healthy soil and grow climate resilience. If we imagine agriculture as a network of entities that grow, exchange, distribute, and consume goods instead of a linear supply chain – then we can work with others in the community and plan land and water quality for future generations.

First and foremost – most folks know that we are certified sustainable by the LISW – the first certified sustainable viticulture program on the east coast. This is important since grapes cover most of the planted area on our farm. Check out their website for details, and look for the logo on local wine bottles.

We have also been wind-powered since 2010 – Russ worked with Southold Town to pave the way for wind power permits on the North Fork. Every year we produce more energy than we consume, so it goes back onto the grid. Weaning farms off fossil fuels is not only smart business, it’s a big opportunity to reduce carbon emissions.

Let’s talk about beef, and here’s where the conversation gets good. Yes, animals can be and should be incorporated into farming – the right way. Beef is a major ‘bad guy’ in the environmental conversation – but grass-fed and pasture rotated is the exception. Converting cropland to pasture and implementing rotational grazing is ideal to establish continuous no-till farming – which is a cornerstone of regenerative ag. When we minimize soil disturbance, we allow the microbial, fungal, and bacterial activity of the soil to thrive and build soil health under a permanent cover of vegetation that traps water, nutrients, and carbon. Rotational grazing also spreads manure over the land where it can be absorbed and fix nitrogen into the earth, rather than run off or concentrate in one place. It prevents the spread of invasives (invasive weeds spread quickly in freshly disturbed soil). Timed right, it also keeps the cows one step ahead of the lifecycle of flies – who lay eggs in manure which cause worms in the herd – so less ‘de-worming’ antibiotics.

Multi-year studies in the Chesapeake Bay region found that converting conventional farmland to rotationally grazed pasture has an average reduction of 42% for net greenhouse gas emissions, and average reductions of 63% nitrogen, 67% phosphorous, and 47% sediment. Our farm used to be potato and corn fields which would be tilled multiple times per year and sprayed with fertilizer and herbicides. Seventeen years later… we have achieved organic certification in our no-till pastureland, a process that Russ has been patiently nudging forward.

Here’s an idea I love… Silvopasture – the practice of intentionally planting trees on grazing land, which is great for the herd because it offers shade and shelter as well as better quality grazing. Plus – more trees is always good. We have been adding native trees to open fields for years now, and will continue to plant.

Streamside forest buffers – Here’s another big opportunity for everyone to consider and implement. It’s ideal to have at least 35 feet of native trees, shrubs, or grasses along waterways. Forest buffers act as natural filters that slow water runoff and allow nutrients to soak into the ground rather than flow into the water and cause algal blooms. Buffers also cool the surrounding land and water and provide refuge for wildlife and pollinators. We border two creeks in Cutchogue – Downs Creek and Halls Creek – and maintain over 200 feet of nature preserve on either side of them. Keeping our remaining estuaries and waterways safe from agriculture and residential use is key to maintaining climate resilience. Anyone with land along waterways should consider planting a natural buffer zone by the water. Wildflowers, beach grasses, rushes, sedges, beach plums, and cedar trees are all great options.

And since we are talking about planting – we should all be aiming for increasing plant diversity and prioritizing native species. Especially plants that provide food for wildlife – oak trees that grow acorns, cherry trees, low bush blueberries, paw paw trees, milkweed for butterflies, coneflower for pollinators – there are so many options. Native plants usually do well in our soils and are deer resistant. We mix them into landscaping, along forest edges, and in fields.

It’s an ongoing conversation, and we are going to keep seeing ourselves through the lens of regenerative agriculture in 2024 and beyond.

Brewster McCall